Journal article published in Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, volume 3, article 2.

Access (free): Weinstein et al. (2018) via doi.org

Scope of Paper

The paper presents six 'cognitive strategies' that can be used as teaching techniques for effective learning. The strategies are based in the cognitive science of learning, and have each received robust support from decades of research.

The six strategies are:

- Spaced practice,

- Interleaving,

- Retrieval practice,

- Elaboration,

- Concrete examples, and

- Dual coding.

Key Findings

When planned for and implemented appropriately, these six cognitive strategies are shown (through a century of research) to improve learning outcomes in students.

They are therefore a practical and useful starting point when planning effective teaching.

The classroom provides many opportunities for combining the strategies outlined:

- Spacing can be particularly potent for learning if it is combined with retrieval practice. The additive benefits of retrieval practice and spacing can be gained by engaging in retrieval practice multiple times (also known as distributed practice).

- Interleaving naturally entails spacing if students interleave old and new material.

- Concrete examples can be both verbal and visual, making use of dual coding. In addition, the strategies of elaboration, concrete examples, and dual coding all work best when used as part of retrieval practice.

More detail

In recent years the teaching profession has made significant progress in applying cognitive processes to effective teaching and learning.

Despite this, very few teacher training textbooks cover these principles, and therefore the strategies are not systematically making their way into the profession.

This paper is specifically written with educators in mind, and is intended to provide practical suggestions of how to implement these six strategies of cognitive science in the classroom.

There is a cohort of teachers that are championing the use of these strategies. They are mainly based in the UK, and are spreading the value of using cognitive psychology in the classroom via Twitter, and through blogs such as Evidence into Practice, My Learning Journey, and The Effortful Educator.

There is a danger that, due to the grassroots nature of this spread of information, some cognitive science is being misapplied in the classroom. This paper aims to clearly illustrate each strategy, with examples of how to properly implement cognitive science through effective teaching.

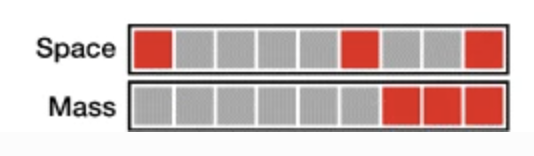

Strategy 1: Spaced Practice

The principle is simple: when compared to massed practice, spaced practice leads to greater retention of that information in the long run.

Massed practice: studying information in one large study session (cramming).

Spaced practice: studying the same amount, but spaced out over time.

Spaced practice mitigates the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve. Ebbinghaus (1885) found that when he spaced out repetitions across 3 days, he could almost halve the number of repetitions necessary to relearn a series of 12 syllables in one day. Since Ebbinghaus, hundreds of studies have reproduced the benefits of the spacing effect.

The theory is explained with a simple mechanical explanation: memories have both 'retrieval strength' and 'storage strength'. Retrieval strength measures the ease with which a memory can be recalled. Storage strength represents the extent to which a memory is truly embedded in the mind.

When studying, both retrieval strength and storage strength receive a boost. However, the extent to which storage strength is boosted depends upon retrieval strength, and the relationship is negative: the greater the current retrieval strength, the smaller the gains in storage strength.

This means that information learned through 'cramming' is rapidly forgotten due to low storage strength. Spacing out learning increases storage strength by allowing retrieval strength to wane before restudy.

Teachers can introduce spacing to their students in two broad ways.

- By creating opportunities to revisit information throughout a term, or even in future terms. This requires planning and can be hard to juggle with the demands of the curriculum. However, spacing can be achieved with no great costs if teachers set aside a few minutes per class to review information from previous lessons.

- By putting the onus to space on the students themselves. Because spacing requires advance planning, it is crucial that the teacher helps students plan their studying.

It is important to note that students may feel less confident when they space their learning than when they cram. This is because spaced learning is harder – but it is this 'desirable difficulty' that helps learning in the long term.

Strategy 2: Interleaving

Interleaving occurs when different ideas or problem types are tackled in a sequence. This is distinct to the more common method of 'blocking', which is attempting multiple versions of the same problem in a given study session.

Interleaving can be applied by setting different types of problems during learning, which is particularly applicable to subjects such as maths and physics. It is found that shuffling maths problems that involved calculating the volume of different shapes resulted in better test performance 1 week later, compared to when students answered multiple problems about the same type of shape in a row.

This is also applicable beyond problem solving: Students who interleaved the study of different painters’ paintings were more successful on a later identification test than participants who studied the paintings blocked by painter.

For problem-based subjects, the interleaving technique is straightforward: simply mix questions on homework and quizzes with previous materials (which takes care of spacing as well).

An important point to consider is that in educational practice, the distinction between spacing and interleaving can be difficult to delineate.

Strategy 3: Retrieval Practice

Retrieval practice involves withdrawing learned information from long term memory, which requires effort, and bringing it into our working memory.

The direct result is that by accessing that learned information, students consolidate that learning, which makes it more retrievable in the future.

We know from a century of research that retrieving knowledge also strengthens that knowledge. As such, a lesser-known benefit of tests is that by requiring the retrieval of information, they actually improve students' memory of the tested information.

There is an indirect benefit of retrieval practice: It highlights to both teacher and student which information has not been retrieved. This provides a focus for future teaching, learning, and review.

In addition to testing, the effectiveness of retrieval-based learning extends to other activities in which retrieval practice can be integrated, such as concept mapping.

Retrieval practice has been shown to be beneficial for learning facts, and also for applying those facts to new situations. However, there is continuing debate as to how retrieval practice benefits more complex material, and as such extra scaffolding and practice is suggested for complex topics.

Practicing retrieval is a powerful way to improve meaningful learning of information, and it is relatively easy to implement in the classroom. Requiring students to practice retrieval can be as simple as asking students to put away their books, and to try to write out everything they know about a topic.

Retrieval-based learning strategies are flexible. Instructors can give students practice tests (e.g., short-answer or multiple-choice), provide open-ended prompts for the students to recall information, or ask their students to create concept maps from memory.

Strategy 4: Elaboration

Elaboration involves connecting new information to pre-existing knowledge, in other words, elaboration involves adding features to an existing memory.

Another mechanism by which elaboration improves learning is via the improvement in organisation of facts in a student's long-term memory. Elaboration involves making information more integrated and organised with existing schema, or knowledge structures.

Elaboration is a broad term and includes many different techniques, so it is not claimed that elaboration always helps learning. One specific elaboration technique with strong evidence for improving learning is 'elaborative interrogation'. Students are to ask 'how' and 'why' questions about the topics they are studying, and to answer those questions using their class materials, and eventually, from memory.

For example, to help figure out how physics explains flight, students might address the following questions: How does a plane take off?; Why does a plane need an engine?; How does the upward force (lift) work?; Why do the wings have a curved upper surface and a flat lower surface?

Teachers can scaffold students in these types of activities by providing self-explanation prompts. The greatest potential benefit of accurate self-explanation or elaboration is that the student will be able to transfer their knowledge to a new situation

Strategy 5: Concrete Examples

Using concrete examples to supplement content that is abstract or conceptual in nature can make the ideas easier to understand and remember. Words that are more concrete are both recognised and recalled better than abstract words.

Concrete examples can provide several advantages to the learning process:

- They can concisely convey information,

- They can provide students with more concrete information that is easier to remember, and

- They can take advantage of the superior memorability of pictures relative to words (see 'Dual Coding' below).

It has been demonstrated that students are able to remember that concrete examples are manifestations of abstract concepts, and use those examples to understand and remember the underlying concepts.

One concern with using concrete examples is that students might only remember the examples and will not be able to transfer their understanding from one example to another, or more broadly to the abstract concept. However, there does not seem to be any evidence that fun relevant examples actually hurt learning by harming memory for important information.

There's a suggestion that concrete examples are widely used by teachers but not widely discussed. A possibility is that they do not consider this a contribution from cognitive psychology.

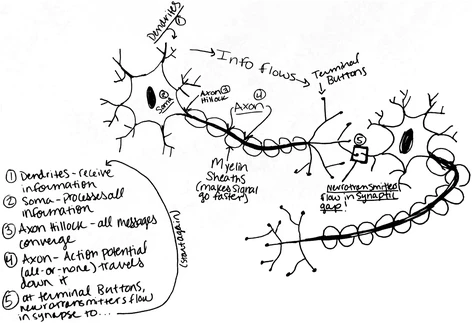

Strategy 6: Dual Coding

Dual coding involves presenting information both through text and the use of images.

The old adage of 'a picture is worth a thousand words' can be traced back to an advertising slogan from the 1920s. It is well-understood that more information can be conveyed through a simple illustration than through several paragraphs of text. Illustrations can be particularly helpful when the described concept involves several parts or steps and is intended for individuals with low prior knowledge.

In addition to being able to convey information more succinctly, pictures are also more memorable than words. In the memory literature, this is referred to as the picture superiority effect, and dual coding theory was developed in part to explain this effect.

There is a danger that when teachers combine words and images, they are not taking advantage of the cognitive strategy of dual coding in the optimal way. Some implementations are not based on evidence, for example, the practice of replacing specific words with images, which is not expected to produce a learning benefit.

The need to be clear about how dual coding is being implemented specifically as a cognitive strategy is important.

The authors present this example as good practice in dual coding:

Note the use of numbers to dual code the imagery with the explanation.

Critically, dual coding is distinct from the theory of 'learning styles', which has no empirical backing from research.

Conclusion

The classroom provides many opportunities for combining the strategies outlined:

- Spacing can be particularly potent for learning if it is combined with retrieval practice. The additive benefits of retrieval practice and spacing can be gained by engaging in retrieval practice multiple times (also known as distributed practice).

- Interleaving naturally entails spacing if students interleave old and new material.

- Concrete examples can be both verbal and visual, making use of dual coding. In addition, the strategies of elaboration, concrete examples, and dual coding all work best when used as part of retrieval practice.