Journal article in The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, forthcoming.

Access (free): von Stumm et al. (2020) via doi.org

Download (under CC BY 4.0)

Scope of Paper

Using a population-based sample of 4,391 students, the authors examine how Ofsted ratings function as a prediction of individual student outcomes. In particular, the paper looks at three specific perspectives on student outcomes:

- Educational achievement,

- School engagement,

- Pupil well-being.

The study uses pupil data on GCSE grades and measures of school engagement and well-being at age 16. The data source is England's National Pupil Database.

Key Findings

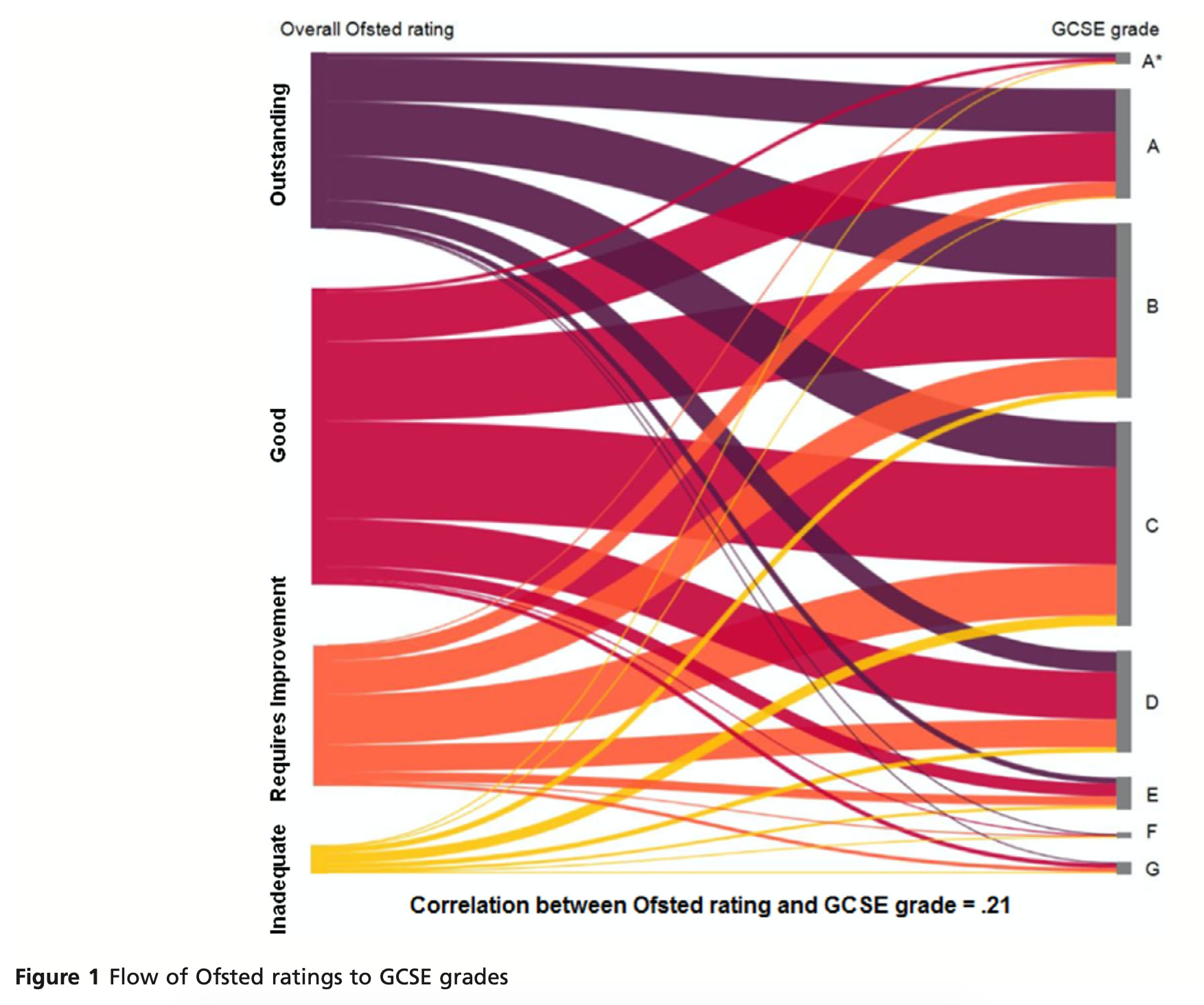

This paper finds that Ofsted ratings have little relation to students' individual outcomes. Ofsted rating correlated .21 with an individual student's GCSE grades.

For the entire cohort, the average GCSE grade of a student at an Outstanding school is 0.94 grades higher than an Inadequate school. This is mostly due to the socioeconomic status and prior attainment of pupils, and not the 'added value' of the school.

When adjusted for these factors, a difference of one Ofsted rating equates to a GCSE grade difference of 0.1 grade.

Students attending ‘Inadequate’-rated schools reported similar levels of happiness, attitudes to school, homework, student–teacher relations, and ambition as those attending ‘Outstanding’-rated schools.

The literature generally agrees that while measures of school quality have a large influence on parents' opinions, they have a small impact on individual outcomes.

More Detail

Background on Ofsted

Ofsted's purpose is to 'inspect and regulate services that care for children and young people'. Their ratings are frequently used by parents when deciding which secondary school to send their children to.

The primary aim of these inspections is to drive improvement within schools and hold them to account. Once an inspection has been conducted, a school is awarded an overall effectiveness rating that informs parents and the government of the quality of education that pupils attending the school receive. In 2018,

- 21% of schools were rated as 'Outstanding',

- 64% as 'Good',

- 11% as 'Requires improvement',

- 4% as 'Inadequate'.

When a school is rated as Outstanding, it can promote interest in the school from parents, students, potential teachers, and has even been shown to increase local house prices.

In contrast, schools rated as Requires improvement or Inadequate suffer repetitional damage. Senior leadership are often removed, and school governors are replaced by an appointed committee.

On average, an Ofsted inspection costs the government £7,200 per school. Schools judged to be 'Good' can expect a one-day inspection every four years. Underperforming schools receive more frequent visits as part of 'special measures', which may result in the school being closed.

Parents, Ofsted, and school quality measures

Ofsted ratings are cited as the second or third most influential factor on parental decisions on where to send their child to secondary school (after location & suitability, and word of mouth from other parents).

Parents rely on Ofsted ratings because they believe that the rating serves as a proxy for the individual outcomes of the students who attend a given school.

However, there is very little prior research on the relationship between Ofsted rating and an individual pupil's education outcomes.

Other measures of school quality have been compared to individual outcomes, and are generally found to have small to moderate association. For example, one study examined three objective markers of school quality (class size, teacher education, teacher experience) and found a weak association with students' test scores in maths and science across 40 countries.

The literature generally agrees that while measures of school quality have a large influence on parents' opinions, they have a small impact on individual outcomes.

Study measures

The study compares the following measures:

- Ofsted rating,

- GCSE grades in maths, English, and science,

- Student-reported school school engagement (at age 16, students answered seven questionnaires about their experience of school engagement),

- Well-being (at age 16, students answered six questionnaires relating to their well-being).

Results

Associations between Ofsted ratings and educational achievement

For the whole cohort, the difference between each Ofsted rating corresponded to approximately one third of a grade at GCSE.

- Difference between Outstanding and Good of 0.34 of a grade,

- Good and Requires improvement of 0.30,

- Requires improvement and Inadequate of 0.33.

- The difference between Outstanding and Inadequate is 0.94 of a grade.

The average grade at Outstanding schools was grade B, compared with grade C at Inadequate schools.

The study found that Ofsted ratings correlated .21 with an individual student's GCSE grades.

Associations between Ofsted ratings and students’ well-being and school engagement

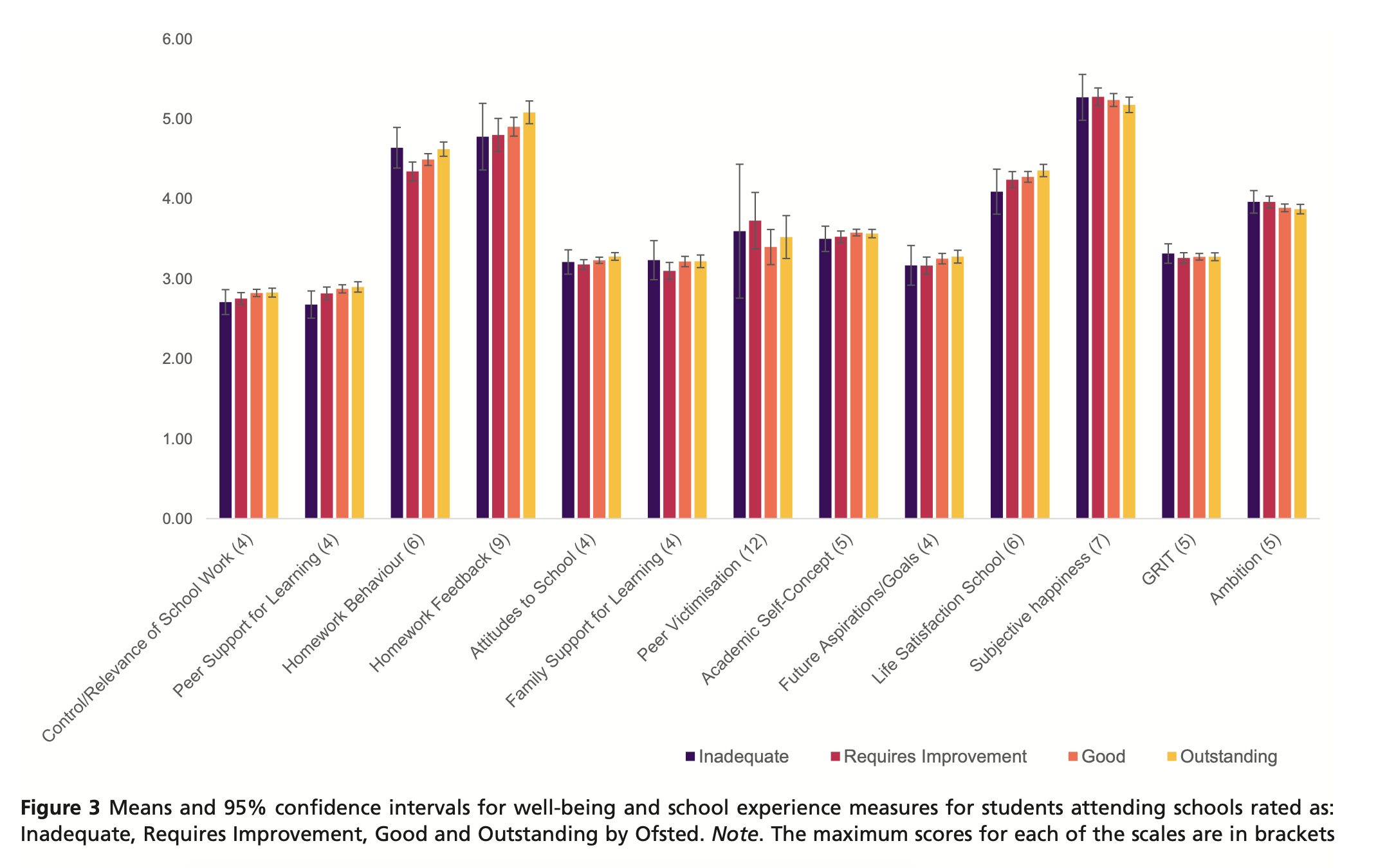

On average, Spearman's correlations between the Ofsted overall quality rating and the 14 student-reported measures of well-being and school engagement were .03. The only significant relationship identified was between Ofsted rating and homework behaviour.

Students attending ‘Inadequate’-rated schools reported similar levels of happiness, attitudes to school, homework, student–teacher relations, and ambition as those attending ‘Outstanding’-rated schools.

Discussion

The authors found that Ofsted rating accounted for 4.4% of the differences in educational achievement at age 16. However, most of this association could be attributed to family socioeconomic status and prior achievement in primary school.

Once these covariates were included, Ofsted ratings of school quality predicted <1% of the observed differences in GCSE examination grades. This finding suggests that even the small benefits of school quality for students’ individual outcomes can be largely attributed to schools’ selection of student intake, and not to their added value.

The authors also found that Ofsted-rated school quality was a weak predictor of student well-being and school engagement. Overall, the findings suggest that individual student outcomes are largely independent of schools’ Ofsted-rated quality.

These findings align with earlier reports that pupils’ individual outcomes show little relation to markers of school quality.

Ofsted states that their ratings ‘allow parents to make informed decisions about where to educate their children’. However, the study finds that factors that parents care about most – educational achievement and students’ well-being – are negligibly predicted by Ofsted ratings. As such, parents may want to prioritise other factors when choosing a secondary school, for example the physical distance between the family home and the school.

Although achievement outcomes are important to parents, they are not the only reason why parents opt to send their children to one school over another. The factors most often cited in the literature on parental choice in education are student happiness, well-being and pupil behaviour. The study finds that the correlations between Ofsted ratings and measures of student well-being and school engagement were very small, and on average nonsignificant.

Students attending schools with the worst Ofsted ratings report similar levels of happiness, bullying, future aspirations, life satisfaction in relation to school, and ambition as those students attending schools with the highest Ofsted ratings.

Conclusion

The study finds that Ofsted-rated school quality is a weak predictor of secondary school outcomes at age 16, including educational achievement, well-being and school engagement.

These findings call into question the usefulness of Ofsted ratings as a guide for parents who are looking to make an informed choice for their children’s secondary school.

Furthermore, the study contests the notion that Ofsted inspections, which are perceived as exhausting, stressful and demoralising by teachers and other school staff, capture differences in school quality that matter for students’ individual outcomes.